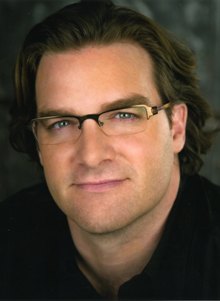

Interview with David Kidder from Clickable

Adrian Bye: Today I am talking with David Kidder, who is the CEO of Clickable. David is located in New York, and Clickable is a pay-per-click company. So, David, maybe you could take it away and tell us a little bit about yourself.

Adrian Bye: Today I am talking with David Kidder, who is the CEO of Clickable. David is located in New York, and Clickable is a pay-per-click company. So, David, maybe you could take it away and tell us a little bit about yourself.David Kidder: Sure. Great to connect with you. I'm based in New York City, founder and CEO as you mentioned of Clickable, and we like to think of ourselves as the kind of Apple of online advertising platforms. We're basically a very simple tool that takes the complexity and time out of managing online advertising across all the major networks, Google, Yahoo, Microsoft and others.

We're about to expand that into the social space. It's really exciting. About 130 people in the company, and we'll add about 100 people in the next 12 months. It's growing very fast.

We raised a bunch of VC money about 20 million from some of the best VCs on the east coast and in the Silicon Valley, same venture capitalists behind Facebook, and Twitter and LinkdIn and others. So we have great contacts on both coasts, and we're growing fast. It's a lot of fun.

This is my third company, so I've been building companies since I graduated from university. I built a mobile advertising firm. Built a 500 person interactive agency in the '90s, and really enjoyed people and building teams and creating value both for my investors and for the employees of the company, and had a great time doing that.

Also, I have two kids, a two and a half and four year old boys, Jack and Steven. Been married for about eight years to Johanna Zeilstra, who is my wife. She's Dutch. We have our third kid due in August this year, which is a total surprise, and wild.

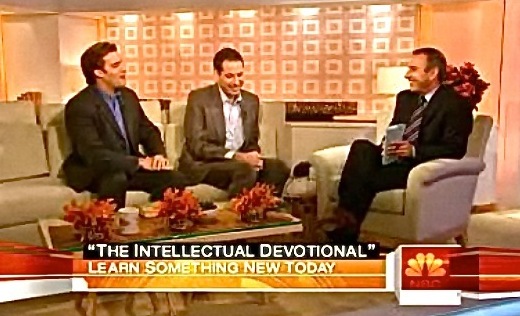

Then I have a couple of side hobbies. One is a book series that I write called, "The Intellectual Devotional." And we do that on Rodale. And it's basically a book series. Our fifth book comes in the spring, in May. It's basically five minute a day readings to kind of renew your mind. And two of the books have been New York Times bestsellers, and a lot of fun.

And then I have a non-profit called GoodAdds which is partnership with GE and NBC and Millennium Promise which helps use corporate branding to market cause-products. So from malaria nets, to inoculations, to Medex, we help use big branding dollars to kind of greed what is good, so to speak. And we use banner ads, and traffic and celebrities to move attention into actual people buying, or purchasing or endorsing cause products that actually do real meaningful good every single day.

Sp those are the big things, Clickable, and the book series, The Intellectual Devotional, and GoodAdds, are kind of professionally speaking, a non-profit. And then family and kids are the rest of my life. So it's a lot, and fun and it's really a very blessed and grateful life.

Adrian Bye: And so you sleep two or three hours a night?

David Kidder: Pretty much. [laughs] There's not a lot of sleep. Especially my wife is pregnant now. Right now she's on our third floor. I'm on the second floor with the two little kids. So it's probably on average, I mean, probably five, I would say, is probably a good solid number.

David Kidder: Pretty much. [laughs] There's not a lot of sleep. Especially my wife is pregnant now. Right now she's on our third floor. I'm on the second floor with the two little kids. So it's probably on average, I mean, probably five, I would say, is probably a good solid number.Adrian Bye: And so you live in New York City?

David Kidder: I lived in New York City for about ten years. And we bought an old Victorian home outside the city, about 18 miles outside the city in Westchester, just north of the city. And we rebuilt and restored this old, old Victorian for about a whole year, about five, six years ago.

Now with two little boys running around like crazy, we've had a great time having light, space and air and having them enjoy that. So we have two dogs. It's a nice break from the city. I drive to the city every day. It takes about 45 minutes and I get kind of some quiet time in the car listening to blogs or podcasts and doing phone calls, so by the time I get home I'm fully engaged with kids. I'm usually with them until about 9:00, and then they go to sleep, and then I work from 9:00 to 1:00 usually. So, it works.

Adrian Bye: You didn't want to stay in the city? Is there a reason you didn't want to stay in the city with kids?

David Kidder: I love the city and I miss the city a great deal. I'm here every day so I kind of get my fix. But the truth is I think, I want my kids to not experience... I think they always have the option to move to the city but they don't have the option not to experience, you know, outdoors and cut grass and sports and those sort of things in a different way.

I don't want my desire to live in the city to take away from their growth experience, you know, outside of a metropolitan environment. That's an option they can choose later in life. It's something we might change our mind on, but for right now with little kids it works out really well.

Adrian Bye: But you have a 45 minute commute each way.

David Kidder: Yeah. It actually can be, depending on how long you leave yourself in the morning, if you leave early, you can get here quicker, but I'd say on average that's about the commute. But my time is fairly organized.

I have an amazing assistant, Susan Green, who used to work at AOL and was Bob Pittman's assistant, and Mike Kelly's assistant, for about ten years. And so she makes every hour two, by booking things really tightly and organized, and creating call-lists, and so we get a lot done. And then we get a chance to kind of decompress between the office and home, and so it's a nice break.

Adrian Bye: Cool. Have you ever had a job?

David Kidder: Have I ever had a job. There was a time after I sold my last...I started a company right out of college called Net-X, which we built and sold over two years. And then I joined to a rollup of a kind of dot-com company in the '90s backed by Omnicom which is the largest agency-holding company in the world.

So during that period I was part of a team. And so to the extent that that was a job, that was the closest thing I've ever had to one in that three years. You know, as part of that team, I worked with that group and that board doing that rollup, so that was probably the closest I ever got.

But I was very entrepreneurial and I was as an entrepreneur amongst other entrepreneurs of the management team. It was a lot of fun. It was wild times in the '90s in New York for the dot-com era. It was very kind of Studio 54, big dollars and crazy. So it was a great period to be in the dot-com boom, and...

Adrian Bye: Do you see yourself retiring as a billionaire?

David Kidder: No, I did make some money, which was great. But, no I don't ever see myself retiring. I think money is not the reason why I work. I love to create and innovate and a lot of my travel in the world has kind of influenced my belief that we have all, in a lot of ways, if we have light, space, and safety, have already won humanity's lottery and we have a responsibility to take risks.

I don't see myself to stop doing that at any one time. I'm not building companies so that I have a specific outcome that makes me have more time for myself. I really want to create, so...

Adrian Bye: And so this is your third company. How did your first two companies do?

David Kidder: So the first one, Net-X, about ten people, sold that to a privately held company that was competing with PointCast and Income Internal Corp Communications.

Adrian Bye: You know you can buy the PointCast today for a couple of thousand dollars.

David Kidder: Is that what it is? That's hilarious. Gives you an idea of how long it's been. That was in '94, '96. We sold, THINK New Ideas, which was this rollup for, I think, 225 to a company that is actually still around, it's called Answerthink. It probably has about two, three thousand employees. And then...

Adrian Bye: You sold for 225 million?

David Kidder: Yep. And then we did, my other, my company called SmartRay, which is a privately held company. We had about 40 people, and we sold that for a little under 40 million after the dot-com crashed. So you know, I had good solid stuff. There's no billion dollar exit fee.

I suspect that Clickable has a very good shot at doing that. I think this will be the biggest company I've had a chance at being, you know, founding and helping build so we're on a very, very fast clip of growth, so adding the scale we have. So I'm very excited about building..

Adrian Bye: So you did a PointCast knockoff, and you sold that for 225 million?

David Kidder: No, no. The point...it was actually in the '90s...it wasn't...we were doing...The company had bought us. Target Vision was doing communications inside of corporations at the desktop and TD level, and so they had a very big footprint of Corp Fortune 1000 companies in the United States where they were the platform for internal corporate communications.

And so PointCast was coming out at the desktop level, if you remember, giving news and corporate information, as well as, obviously, just general news. And so they bought my company Net-X to help build the Internet platform.

Adrian Bye: Oh, they bought your company?

David Kidder: Yes. To compete with it. And then I, after about a year, I left to go move back to New York, or move to New York, and do the roll up, that then became, we did a roll up actually went public from 80 employees to 500 like in two years. We bought like eight companies. It was a wild run, and then...

Adrian Bye: I'm really interested to understand. This is a really interesting perspective. You've been through the wild times of the dot-com era, and you weren't in Silicon Valley, but obviously you were interacting a lot with those guys, and you were in what I think of as the new capital of the world that is New York...

David Kidder: Yeah.

Adrian Bye: How was it? I mean obviously we know today in hindsight, and this is ten years later, so it's easy to look back in hindsight and say, well those guys sucked and they're wrong, but nobody knew that back in the time.

David Kidder: Yeah.

Adrian Bye: How did that feel at the time? Did you doubt some of the stuff that was going on? How were these things happening when there wasn't a proper financial underpinning to it all? How did it feel? Were people doubting that? Or were they like, this is the thing, and we are just going to go for it?

David Kidder: Yeah. Well, I think we are all pretty wide-eyed. I don't think that people realized that we were really in the first generation of that technology. So, the Internet affected so many public conscious minds, both privately, and publicly, personally, and professionally, that the hope was transformative across every sector. So you had everybody dazzled, whether it be a start-up person, right down to your grandmother. You had everybody who is touching this technology.

So I think that's why the accentuation of that, and the arise of those technology companies, and the IPs and stuff, was so dramatic, because everyone wanted to be a part of creating that, and participating in that technology. It's not like nanotechnology, or energy, or derivative products, where only 10 people know how to do it. Everybody understood it. So, very few technologies have that type of vocation that are not just an investment. That are not participating investments. And that's why it got so hyperbolic in its growth.

And by comparison, the dot com boom looks like a small mistake compared to what Wall Street has done to Main Street. So it is important to have that context. Yes, it was a discreet financial over accentuation of value. OK. Great. So, they launched 500 IPOs and created a half a trillion in value, or a trillion dollars in value. Seventy five percent of that went away.

However, you birthed very serious companies. You birthed Amazon, eBay, Google. You built monsters. And you also invented the first generation companies to Facebook. Like the Globe, and Six Apart, who holds those patents to those next generation of technologies where people, and adoption of behavior became real, and did that.

So I think that first phase was as much an economic hothouse, as was art hothouse. And it really did incubate what is now the platform you saw, even this last week, it is the first year that there will be more dollars spent on digital advertising than analog. Ecommerce is projected to do $259 billion in total sales in those platforms over the next five years. Those are completely disruptive shifts in behavior, and technology.

Adrian Bye: Because I think Chris Anderson had said that in that first decade, as you mentioned eBay, Amazon, and Google, and a bunch of others. In this following decade we've only really had Facebook, and potentially Twitter. There hasn't been a ton more that has come out of the second decade compared to the first decade.

David Kidder: Google really straddled the decades. Google was formed in 2001, 2002 and really went public in 2004, 2005. So Google was borne out of that. Which is far and away the most dominate piece of technology ever created on the Internet.

David Kidder: Google really straddled the decades. Google was formed in 2001, 2002 and really went public in 2004, 2005. So Google was borne out of that. Which is far and away the most dominate piece of technology ever created on the Internet.Adrian Bye: But Google was formed in like '98, '99.

David Kidder: I think it was actually 2000, 2001. It was in a university at that time. But by the time it was actually scaled it was 2001-2004 the revenues grew like seven million to 50-60 million. And then, after they created the auction of PPC, in 2004, is when they really exploded.

That was being incubated and started right after the whole...Yahoo had gone public. Go To had gone public. All these companies that were doing kind of directory based search indexes. They just reinvented the second generation. So I kind of put them in that next bucket.

But Chris is right. Chris is actually a friend and a neighbor to us here, and Silicon Alley is right across the street. I could probably see his office through here. Chris is right in a sense that we have formative, cultural, and business changing businesses. You still have businesses that are emerging. YouTube is a transformative type of success, that was not a fluke.

You have smaller less capital intensive businesses, that may have not moved the economic needle, but they've moved behavior. The economic rule for behavior shift, Amazon, eBay, Google, have been great.

But there's also tons of other applications that maybe have not been worth a billion dollars, but have created hundreds of millions of dollars of behavioral value. Take Craigslist for instance. Craig Newmark created that business, and he's doing $50-100 million in revenue. And he destroyed a five billion dollar business of the Yellow Pages.

Adrian Bye: Well, it's not just the Yellow Pages, there are newspapers as well.

David Kidder: Yeah. That's a great point. As much destruction and disruption as has been economic value being created, ideologically speaking. The stack was created in the first generation. And now everybody is building on the stack, building on APIs. Less expensive businesses to create maybe less economic reward at the exit, but still. Huge disruptive values being created all the time. Location based technologies.

Adrian Bye: Well, even so, the disruptive value is like maybe 10 percent of what was there before. Craig Newmark, 50-100 million a year, but if he's taken out newspapers, and the Yellow Pages. The revenue he's generating...I guess it's value that is going up in society instead of being captured by corporations.

David Kidder: Yeah. And maybe that's not a bad thing. I don't think that's a bad thing personally. I don't think there's dynastic evolution in technology. I think it's disruptive and destructive technology of evolution.

And so the fact that those mainstay companies who own media or own knowledge, those sort of things, necessarily deserve or are in a position culturally to maintain it. I think that destruction happens much faster. So the idea that suddenly the newspapers are the ones to figure out how to save their business before it drives off a cliff. That's a myth. And not necessarily. You can have all the major newspapers drive off a cliff with no answer to the problem. And it could take a 10 year window to actually fix that problem. And it may not happen because all the journalists figure out how to monetize their skill.

It could actually happen because a technology like the iPad, picks it up, and runs with it. or the Kindle. It could be hardware related. So I just think we are in a highly volatile, high vibration moment, where the owners historical economic value for information knowledge technology, are on the hook for solving these problems, but are unlikely to solve them because of a cultural bias, and talent.

Adrian Bye: Do you think you would be starting your third start-up of Clickable today if you had been born in Nebraska, and grew up in Nebraska?

David Kidder: Well, it would be available to me. I think the distance, and proximity is not an impediment to starting companies. I love how Mark Andreeson who always says, it's always a great time to start a company, good or bad markets.

I do believe that location definitely influences the speed in which you can grow a company. You need to put yourself physically into a place, a grid so to speak, of inter-networks. A graph, so to speak, where the connections, and the relationships you have, actually accentuate your business. New York is a great place for that. Silicon Valley is a great place for that.

There are other markets, but there are very few that are like those two. They make you go faster. Your inner connection is going to be greater. Therefore, relationships are formed faster. Attention is provided more discreetly. And you grow faster. You are the one to get the deals first. They're network values.

I was at TED this year. There was a great talk about is obesity viral. Can you actually catch obesity, as almost like an allergy? And they looked at all the data, and statistically you can. Your friends, and their friends influence your weight. In the same sense that your success is influenced by you, and your friends. So it's the same concept, and tipping point.

There are mavens in your life. There are maven individuals. There are maven places to live. There are maven companies that can transform your entire outlook of your business. I have experienced that, and I try to be one myself. But it's very important where you are. It's available to you if you want to live in Nebraska.

Adrian Bye: I have heard from people that have been at TED, that they say that you don't actually get to meet people that much. That it's more like you are just sitting there for the presentation. Then you are running off to the next presentation.

David Kidder: There is a lot going on. I should know, because I am friends with the founder and his wife, so I am biased. I think it is the greatest networking event that there is in the US. There is no other place where you can roam around under security and see Bill Gates hanging out, walking around. Jeff Bezos, some of the most powerful people in media. And the talent in the room of people is absurd.

I was sitting down having a cup of coffee by myself when a woman sat down next to me. Just talked for a half an hour. I did a TED university talk two years ago on a concept called the Board of Life, which we can talk about later. And she came up and talked about how that influenced her a great deal. Her name is Amanda Briggs. And she is like the chief trend spotting officer for all of Nike. Where else do you meet people like that? And she's there. And they are there for four days.

People won't just come, and speak, and leave. They are fully engaged 8-10 hours a day. And you can meet anybody in the world who's there. It's just incredible. So people on the outside when they criticize it for being a little elite or less informative, they are just wrong. It is everything it's talked up to be. It is extraordinary. I hosted a dinner party...

Adrian Bye: While you were there you did actually go and get to meet a lot of people. It wasn't just...

David Kidder: Oh, it's networking on steroids. It's so powerful. Everyday I had breakfast and lunch... Actually I invested in it quite a bit. I host a dinner party with two other founding friends, Jack Meijers and Mark Cinadelladders. We hosted a dinner party for 120 people. It's called the TEDster's New Yorker's Dinner. Just to kind of do a small group and get connected. And it is worth it because you're building relationships and after doing it for four, five, six years, it's just access and relationships. It's very, very authentic. Beyond learning, which is extraordinary. It is that.

David Kidder: Oh, it's networking on steroids. It's so powerful. Everyday I had breakfast and lunch... Actually I invested in it quite a bit. I host a dinner party with two other founding friends, Jack Meijers and Mark Cinadelladders. We hosted a dinner party for 120 people. It's called the TEDster's New Yorker's Dinner. Just to kind of do a small group and get connected. And it is worth it because you're building relationships and after doing it for four, five, six years, it's just access and relationships. It's very, very authentic. Beyond learning, which is extraordinary. It is that.I am a huge fan of it. I have been to a lot of conferences. And I still do it. I think it is one of the best.

Adrian Bye: So did you go up and shake hands with Bill Gates?

David Kidder: I have about two years ago, no, the last one, 2008. But, yes. I am not on a first name basis with him but he is very accessible and present. He is an extraordinary man.

Adrian Bye: Was he there for the whole four days?

David Kidder: Yep. Yep, the whole time. As is...

Adrian Bye: Did he like look down at you and say, well [Inaudible 20:44] ?

David Kidder: [laughs] No. He is actually incredibly present. He comes across as quite a sage, and kind, and thinks about very big ideas. He is very direct and very confident and those sort of things. But he has got a very kind soul. His persona is there is a lot of urgency and importance to his work for the Gates Foundation and energy and those sort of things. So he is kind but he is also a serious man. So he comes across that way and is present that way. But he does walk around with a smile, he's got a great sense of humor, and he's accessible.

I think people give the more celebrity personalities there, the artists, the actors, the CEOs who are more well known, their space so they get a chance to actually rest and learn, and that sort of stuff. But it is available to you if you want to meet them.

Adrian Bye: Actually, I just want to ask you a little bit more about it.

David Kidder: Yeah.

Adrian Bye: Being in New York, do you feel that's given you more access to more deals and more info? You're around the mavens obviously networking. So do you really feel that strongly has helped you a lot, has it?

David Kidder: Yeah, definitely.

I have invested, I think authentically, in building very good relationships with people who are doing important work and I try to cultivate that a lot. Again, you can't fake that stuff; it has to be real.

I feel like I have some of the best venture capital money in New York with the Union Square Ventures, Fred Wilson, Albert Wenger, and Brad Burnham. And then, I have the Founders Fund on the West Coast in Silicon Valley, which are the guys who founded PayPal, formed Adventure Capital Fund and other key VCs behind Facebook, LinkedIn, Slide, and a bunch of great companies there. So I have good access on both the East Coast and West Coast.

They're very different places to build companies. New York is very media advertising rich, but the entrepreneurial community is very strong. So we're still a distant second from Silicon Valley but I'll have to say that the startup community here is very vibrant. It is growing very fast. We are probably second only to Silicon Valley. I think we will never exceed Silicon Valley. It is just different.

I think it is still one of the second best places to build companies, perhaps, and we are getting there. Silicon Valley, obviously, has lots and lots and lots of people who have built and sold companies, better entrepreneur base, better technology. I'll just say that I rarely have to travel. The good point is that in this next generation of technology, with media and advertising driving these conversations, that's all done in New York. So all the major deals I do are in the city, which is a huge competitive advantage over the valley.

But when I have to go do partnerships with Facebook and other people, I have to travel. I have to go see the platform companies out there. So another way to describe it is, they are building a stack of technologies and we are building on top of it. Now they are both expressing different types of value, but they are also unique and discreet in how they trade it. So I am very bullish on New York and where it is going.

Adrian Bye: If they're building the stack and you're building on top of that, does that mean they're the ones that get the billion dollar evaluations, you get the hundred million dollar evaluations?

David Kidder: It's possible. I think it's a function of evaluation of the company, both revenue and behavior, and so as people switch behavior into your network the stack becomes less important but the stack is always important for more core IP values. So we'll see how that plays out.

There's a great paper that I read that really shaped my thinking on just business and where it's going. It was in February 2006. It was called "Eager Sellers and Stony Buyers." It was in Harvard Business Review and it described market friction. So, there is always an incumbent and competitor in every marketplace. The incumbent has a huge advantage over the competitor in the sense that it actually provided statistics that prove that.

So take Google or Yahoo or something as simple as insurance, Allstate versus GEICO, or detergent, Cheer versus Tide, it doesn't really matter, Dove soap versus Old Spice - whatever. The point is that to get someone to move from one behavior to another you need to convince them that there is a better RLI, that it is unique, it's different, and it creates a lot of liquidity for them. So that's a natural three-x hurdle.

But this paper actually proved that there's another three x hurdle that's compound. So there's actually a nine-x hurdle between Google and Yahoo, GEICO versus Allstate, Tide versus Cheer, all those things. And that compounding second variable is user behavior. OK?

So the point is that it is extremely hard to get customers to switch to what you're offering. The only way to beat market friction is through cost. You can do it for free. You can make it easier, simpler, or you can do it for them. So you have got to create a transom by which behavior and trends and stuff switch.

A way to think about that is, if you are in the switching business and you can get people to switch behaviors to your product, which is kind of like built on top of the stack, you can create tremendous, tremendous value. If you own the incumbency and you are building on the stack, then the stack has more value. So depending on the marketplace where if you are on the stack versus the user experience, you can create billions or hundreds of millions depending on how valuable that is to the marketplace.

Another way of saying this is it is better to build painkillers than vitamins. OK? Vitamins are elective. Painkillers are required. Painkillers are worth a hundred times more than a vitamin company. And you have to be able to solve these problems simply to feed the friction and create an equal value for the customer to switch to what you're doing.

Adrian Bye: So has that guided your business, ultimately?

David Kidder: Absolutely. I am in the painkilling business so I go into huge marketplaces where there's lots of pain and I try to create simple, beautiful answers to that pain. I try to create such demonstrable value that can be easily understood and...

David Kidder: Absolutely. I am in the painkilling business so I go into huge marketplaces where there's lots of pain and I try to create simple, beautiful answers to that pain. I try to create such demonstrable value that can be easily understood and...Adrian Bye: The way you are saying it is what we would say in direct response is in direct response we know we want to sell a solution to a painful problem; we don't want to sell a preventative.

David Kidder: Yeah.

Adrian Bye: Preventatives are real nice but people don't spend lots of money on preventatives. They spend money on cures.

David Kidder: That's great. This is just a twist on that or it is a very similar way to express the same point. Yep.

Adrian Bye: And something I want to talk about in a moment. But just before we do, I am interested to understand your thoughts on how you took financing. You're obviously got a lot of options and you chose to work with Fred Wilson and Union Square Ventures. You're working with the guys down in Silicon Valley. Why did you pick, effectively, blue chip money rather than cheaper money because I am sure you have a lot of cheap money around you too?

David Kidder: Well, Fred, Albert, and Brad at USV are incredibly pro entrepreneur. They understand that they're in the talent business. They're experienced so they have been in this business for a long time. And they are very different from the Founder's Fund. The Founder's Fund is young guns, young entrepreneurs who are also profounder. But I would just say that in both instances our third [base?] VC by the way is FirstMark, which is formerly Pequot with Rick Heitzmann.

I would say all three funds who are involved with us all understand that building companies is an art, that it is a science. It's very difficult to do it well. So they have all built and sold companies. Many of them have operated businesses. So they are so pro-entrepreneur and they so understand the complexities, it takes a long time to build a company, that you know that they are going to be there the whole path.

They are also very connected. And so being connected and having a long-term vision of building great value I realize give you enough air room to speak at the boardroom to deploy capital and spend money well towards solving these problems. So they are not impatient and they are with you. So I think I had a good fortune of working with them and I have a lot of choices, quite frankly -- and I also did take, in some instances, a lower valuation to work with them.

Because it's better to win well with all your investors intact who were believing in you, and get the "win, " so to speak, and solve those problems, than it is to go for massive valuation and not have your investors come along with your own success and be helpful for the business.

Adrian Bye: You're in Manhattan. There's plenty of old money there. There's the Vanderbilts, there's Rockefellers. I would imagine with the networking you've done, you probably know some people from the Rockefeller family.

Why not get some of those guys to give you money at a lot cheaper rate? Kind of set their expectations in advance, like, "OK, Rockefellers, you're not going to get this money back for five or 10 years. You may lose it all. I'm already networking enough so that I can replace the networking that the blue chip VCs have, and we'll just do this this way. And that way you'll make a lot more money, and so will I, and it'll be better for both of us."

David Kidder: Well, it's more than money. There's incredible advice that comes with that. There's contacts that come with that. There's accountability, knowing that there's a positive pressure on a company. You don't want to let your investors down when they're reputation makers in the marketplace.

I think it's important that you have a board who's helping drive the business, that they're helpful in doing it. But we meet every month. And we are, I feel, and the company feels, accountable to being a good steward of their capital. And we're a better company because of that. I wouldn't necessarily feel that if it was the Rockefeller money, that if we lost it, it would affect their life at all. But I know that the returns that Albert and Fred and Rick at FirstMark and The Founders Fund is on for, and they've entrusted that with me.

And my leadership is real. And so I take it very, very seriously, about how I'm building this company. That we are working in concert to create the greatest economic value for everyone around the table -- all the employees, the investors, and their investors. And we're a better company as a result of that. We've done this before. We're good operators. Our investors are not all over us. I would just say that that sense of accountability drives this business. We're trying to create incredible economic value and market value for everyone.

Adrian Bye: And so that justifies a lot of valuation, because you think in the longer term the accountability will help you get there, and then just the resources that they bring to the table are going to make it a lot better.

David Kidder: Another valuation I used in one instance -- it wasn't significant, by the way, but it is material ... Let me just say this. It's hard to build a company, first of all. But it's also hard to sell a company. It's hard to make money, period. You have to have the entire marketplace want to see you win. Your employees want to see you win, your competitors, in a way, have to see you win; your customers want to see you win. The company that buys you wants to see you win, and be enriched.

So you need incredible good fortune and luck, and all those things stacked in your favor, to build something to really dominate a marketplace. And so, the conversations and the reputation that happen as a result of your VCs engaging with you can transform the value. Because they're having the conversations with the investing community, with the corporate development officers of the companies that sit down and look at their portfolio of investments and say ...

It's almost like shopping. They're opened up and saying, "Here's what I've invested in. What do you like?" And so, if you're not part of that conversation and/or you're not getting a disproportionate amount of influence in your speed, it does hurt the company unless you're just so good that you don't need any of that. And I think there are very few companies that are just so good that they don't need market advantage to grow fast.

VCs don't make a company successful. I think they help make a company make better decisions and grow faster. And that's it. Still, at the end of the day it's about the magic of the entrepreneurs, the magic of the culture, and the magic of the product at the right time in the marketplace. That is the bet. They do help, but they don't guarantee success. Raising money, it's a material event, but it just means you can start building. It's not a signal that the outcome is going to be a success. It's just empowerment.

Adrian Bye: Interesting. OK. Can you tell us a little bit about Clickable? It's your third company. You've really focused on building a strong team. You've raised a bunch of money. Tell us about what you've been doing.

David Kidder: The players in the marketplace sell complexity. Most companies in the marketplace describe how hard it is to do this, and then they sell solutions to that difficulty or that complexity. Or, they say that their knowledge, their technology, is the only thing that can solve that complexity.

And between companies when I did a lot of research, I thought, this marketplace is just desperate for someone to come in and just speak truth, to speak simplicity, to speak in common, and transparency. I wanted to express a lot of my work experience and personal and professional interest in those areas, about creating a culture that's designed to solve those problems and to do it in a trusted way for companies.

It's also huge, too, so there's a lot of room to maneuver. There's a lot of room to invent. It's not like one answer will solve your problem. You can have lots of different flavors, so to speak, or outcomes of the company that you can invent. And that means that you can become something different, have great success, as long as you have optionality in front of you.

A company growing fast needs to go in and create a solution to a problem but it typically takes three years to really figure out what you have. You go with a bias and you try to solve that bias. But the truth is, you need to build it backwards. You need to listen to the customer, look at that and build that. Let the marketplace rip the product out of you. And that's what we experienced.

After about three years of working hard and solving that problem and being capitalized, you're going to discover what you should be in the first iteration of that company. And we're kind of there, now. We're hitting our stride, but it's a slog. It's complex and challenging and high risk. There's a lot ways to kind of fumble the opportunity along the way. But if you keep the business solving those problems, simple, and you're not trying to boil the ocean, you can get to the answers and fast, and create a great company.

I admire Steve Jobs a great deal. I studied industrial design and fine arts, as well as engineering. So I love design and beauty in product. We try to be that. We try to create a unique, powerfully simple user experience across all these networks so that anybody can come in and experience success. We give them recommendations.

We have a very sophisticated piece of technology called an Act Engine, which is about a hundred algorithms, and a bunch of quants who built it. It just basically tells you how you're doing and what you need to do every day, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

They're just simple recommendations. But the hardest thing in the world is to do something simple. It's easy to make things complex. It's easy to add features and buttons and switches and knobs and language and words. But it's very, very difficult to take those tools out and just give the answer, and/or ...

Adrian Bye: And so you've focused on making it simple.

David Yes. Which is very hard work.

Adrian Bye: So, how do I pay you? Because I can obviously go to Google and Yahoo and Microsoft and run my campaigns myself. How do I pay you? Is it a percent, or is it a monthly? And then why would I pay you rather than go and manage them myself?

David Kidder: It's a percentage of your spend, typically two to five percent of everything you spend on top. We get compensated that way. Your success is our success. [Coughs] Excuse me.

The reason why you'd use us is because we save you time and defeat complexity. The type of people that we're chasing -- the 100,000 companies spending between $2,000 and say, $100,000 a month on Google today -- are doing five jobs. OK? And so they have so much work to do that they have Google and Microsoft Excel open, trying to develop "A Beautiful Mind," so to speak, on how to do this business well and make money. It's a full-time job. It's actually two full-time jobs.

We make that 15 minutes a day. We produce a greater economic return, because we disrupt the complexity and we do it for you. We grab one hand of the wheel, you have the other, you own your data. We give you a brand new simple experience, and we set you on a new course.

Adrian Bye: A lot of it sounds like customizing a Google pay-per-click campaign. It's pretty complicated, though.

David Kidder: It's very complicated. And we disrupt that complexity.

Adrian Bye: It's very custom. Do you think that you're doing it with systems, rather than with people?

David Kidder: It's a balance of the two, but we give you the tools. Our recommendations will actually tell you what to do. We would look at your data and say, "You need to change your ad campaign. You need to be changing the structure. You need to add these keywords. You need to increase these bids, decrease these bids." All those things, all through a simple two-three step wizard.

So after the first month, you've reshaped your entire campaign by forcing these hundred-plus algorithms representing best practices and the math, the bid management, against the campaign. So we actually every single day run a user analysis over your campaign data to enforce the best practices. We're defeating the entropy. We're making the keeping a hundred balls in the air simple by just holding them up for you. Now, you have to do a little bit of work intellectually but you, the effort of identifying those problems in those two areas, we solve for them.

We also have a program called Clickable Assist so if you don't want to do it we'll just do it for you, so you could just hand it off to one of our teams who has a bunch of technology that actually allows them to do this well. So there's a nice balance between, you know, you having one hand on the wheel, us having the other, us having both for a period of time, and, the point is that we just defeat time and complexity. We make the average performance marketer bionic: better, stronger and faster than they really are. It's like.

Adrian Bye: But over time where do you end up? Like a few years ago, web analytics was a big area and then Google just bought.

David Kidder: Yep.

Adrian Bye: Urchin I guess and basically like removed that space.

David Kidder: Yeah.

Adrian Bye: What's to stop Google doing that from AdWords, which I mean, I guess we could assume will happen at some point, next year they won't be allowed to do systems to manage Yahoo and Microsoft but maybe they'll do it anyway and then suddenly everyone just uses Google doing what you're doing.

David Kidder: Well they can do that today already. There already is choice. A customer, any one of our customers is already using Google Directory. We're just giving them a different experience. And so we work very much in concert with Google's goals which is to you know, make these advertisers better than they really are. And so we're solving some pain for Google which is, we're expressing AdWords and Yahoo and other, Microsoft and Yowzer in a different way. And so, we're giving the marketplace choice, we're giving the marketplace simplicity where there is complexity.

Google's going to make the same amount of money, but we make marketers spend more money with Google, more effectively, faster than anybody in the marketplace. That's a good thing. It's a good thing for Google, it's a good thing for us and we're rewarded by that economically. We're solving a major market problem for them which is, not everybody can be successful at Google. We make more people successful at Google than Google can on their own.

Adrian Bye: What's a typical, like a real success story to come through you? Someone spending fifty grand a month and you get them up to a hundred and fifty grand a month? I mean what's that look like?

David Kidder: It's not only how much money they're spending, it's how effective their goals is being set so it's.

Adrian Bye: No, I'm assuming that's not branding driven, that's totally possible.

David Kidder: Yeah, it's conversion driven. Now what is their goal? I mean it could be downloading a white paper, it could be selling a product. And so the conversion value, the ROI, or the effective you know cost per acquisition is one of the key metrics of this. But what's important in the marketplace is that where there's lots of people selling lots of complexity, is to simply ask the advertiser, here's a wildly inventive question, "What is your goal?"

And accomplish that goal. Ninety nine percent of the marketplace has simple goals, they're not, you know my friend, you know the founder of Zappos, has a million products selling, that's complex, most customers have less than ten. Can you make them successful selling less than ten products, all tagged and optimized simply. And do it in 15 minutes a day as opposed to ten hours a day and we do that.

And I think that that's, we're also independent. So we're a third party company validating the ROI across the networks. That's very critical is that we are transparent and we're trusted and we're independent. And it's a very, very valuable thing for this marketplace to have is someone who's saying, "Here's how you can be successful doing this simply, " and be objective, as opposed to the networks owning the relationship and there's an inherent mistrust because the more effective and efficient an advertiser is in Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, the more money they make. So, you have an opposed market value with the advertiser and the network.

Adrian Bye: So what's a typical client for you guys?

David Kidder: Well we, you know someone spending between $2000 and say a 100,000 a month in online advertising inside of Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft. We have some customers, I mean that's not the ceiling, that's the average so I mean, we can go way up, and we have huge spenders and we also have smaller spenders. But I think that kind of, maybe the key KPI, towards, is you know, are they selling, do they have a complex goal or a simple goal. And again 99 percent of the marketplace has a simple goal.

And so it really allows us to chase almost the entire marketplace, while we're very disciplined in our targeting, we can provide a value for lots of customers, but I, you know the spirit of this is, this isn't a Clickable commercial this conversation I think what I'm trying to do is seed how we think about the world. And being different and contrarian a little bit, you know, we're zagging for the speak where lots of companies are zigging, we're trying to disrupt the conversation in the marketplace on simplicity and transparency and community around solving these problems.

And I think that our product is, I think is probably the best in the world doing that today, while we're kind of trusted and.

Adrian Bye: Let me just jump in because we're running low on time and I want to go through a bunch of questions if you don't mind.

David Kidder: Yeah.

Adrian Bye: Do you see yourself staying with search or do you want to expand out to other kinds of inventory?

David Kidder: We're definitely expanding. You're going to see announcements from us in social in the next, you know, two months or less. We're doing deals with every major social network, we're doing deals with real time networks, all those things, I can't speak to them but they're you know they're confidential but there's a lot of, we're going wide, we're going to bring value across.

Adrian Bye: So more of an advertising inventory site, banners or video or other stuff.

David Kidder: Banners, social, local, mobile, the whole thing.

Adrian Bye: So you, so basically you want to become an ad serving platform.

David Kidder: I want to be, we want to be, we want to be the Apple of ad management platforms. The serving piece is done as kind of a third generation technology, we want it to sit, we want to be on the desktop of the marketer, helping them be great at this business.

Adrian Bye: So I interviewed Frank Adante from the Rubicom company.

David Kidder: Yeah, Frank's great, he's a friend, he's a great guy.

Adrian Bye: Yeah he's a cool guy. And he, the interview when we had it was about them building out an ad server to help publish it and that was, they were going to optimize, I think their cut was nine percent of the spend.

David Kidder: Yep.

Adrian Bye: And be able to optimize and show ads more efficiently.

David Kidder: Yep.

Adrian Bye: So it's slightly different to what you're doing.

David Kidder: Yeah, they're the publisher side we're the advertiser side.

Adrian Bye: It's publisher rather than advertiser driven, and I haven't spoken to Frank in awhile, but I've seen just in the last couple of weeks they've made a big switch saying, "Kill the Ad server, " like ad servers no more. I don't quite understand what's happened there but it seems like they're making a pretty big change and actually I'm going to be talking to Frank about it fairly soon, I'm interested in what you think of that and how that relates to what you're doing, how what you're doing's different.

David Kidder: They're unrelated. I mean we are in a different marketplace. They're the display, inventory or just the brand inventory of publishers and we're on the performance side of the marketplace for advertisers. So very, very different, apples to oranges. I'm not really close enough to display to give you a highly credible opinion, but, I think, you know, Frank is smart and he's also got great investors behind him so they're trying to, I think what they're recognizing is that the publishers, the big, big, publishers are taking back their inventory.

There's so much inventory I think it was like 2.7 billion display ads last year and it's growing ten percent a year as a compound constant, it's always growing, compounding, is that there's so much inventory that pricing is going down. So even if you know, Frank built the greatest serving technology, optimization technology in the world and he's got very good stuff, there's so much volume through it they can't affect pricing so the point is, how do you create pricing?

You create scarcity, you have to take volume out of the inventory and so on both systems better ad serving technology and better targeting doesn't necessarily, while it can make the ads better, it doesn't affect price. So targeting, the best targeting technology in the world, isn't going to necessarily over time going to be able to defeat the amount of depressions that are in the marketplace.

Adrian Bye: I mean, if you have a system doing a good job optimizing and you're able to get a CPM from a dollar up to a dollar fifty by having a broader inventory of advertising to show, that's increasing pricing, I mean even if you decrease cost you increase volume.

David Kidder: It's true, but if I'm a premium, if I'm Time Magazine and I'm using Frank's technology or his competitors' and I can increase that retina inventory from a dollar to a dollar fifty, but I can also just stop giving you that inventory. I can just say, "You know what? I'm going to just sell this inventory myself for $20 CPM's, that's the transformation, is the price. Playing scarcity. Selling less inventory in fewer places and selling it direct.

That's transformative. And I think the trend in large publishers is that and so I think, Frank is very smart, he's going to find a way to create value at the highest leveraged price of display inventory both at a market position and technology innovation, he's got a great Board.

Adrian Bye: So you don't have that problem because you don't have the inventory going wider you just have to do a better job for the advertiser.

David Kidder: That's right, we're in a very, very different marketplace. We're both bringing simplicity to a complex problem, but we're doing it from very different inventory stacks and very different type of owners, so to speak. Advertisers versus publishers. But, I know those guys are very clever and one of his board members is a friend, Raj Capur from Mayfield and he's a, I would bet on them because they're smart.

Adrian Bye: No, Frank's a bright guy. So let's say things work out really well for you and you're growing, who's the sort of company that ends up buying your company?

David Kidder: You know, it's the type of company that, first of all there's a lot in our space who could be potential owners so there's a lot of kind of natural owners of this company.

Adrian Bye: That's exactly what Tony, Tony from Zappos does where he says, "Oh no, we're never going to get bought."

David Kidder: Yep, right. Exactly. Tony is great, by the way. Yeah. No I think that we will be. Right now we're building a standalone company. I think this company is scaling very, very fast. Faster than I thought. It's like, I think, every month we grow further. We are gaining momentum. We are not just building into the plan. I think it's going to be leveraged and compounded growth over the next three or four months and then who knows what is going to happen. We are on schedule with 112 people the next 12 months and then beyond that it could be a lot more. So I am excited about that step.

I would say this. The purpose of Clickable, and this is the thing I talk about every month with the whole staff, is that the purpose of Clickable is to help companies survive and thrive by making online advertising simple. Our purpose is to put food on the table and to allow us to hire people and grow. So while we have lots of partners who can use us and potentially buy us, we'll never do anything that violates that truth about us. Our customer is the business who is trying to grow, to literally put food on the table and we talk about it in a testimonial every month.

So there is very deep meaning here that is meeting out[?] culture. We have very clear values. There are three things that we believe in. The first one is this rule called the seven to one rule. Which is we individually to each other and to our customers try to do extraordinarily more good then we do bad. We admit that people, product, and data are not perfect. We are incredibly honest and directly transparent because there's no contempt in this culture. We are out there to solve these problems and to do it transparently.

Now if that ratio starts to shift negatively then you're probably not the right cultural set. But that rule and that belief allows the spirit of this company to live that out and with a lot of forgiveness but also excellence.

Our second value is that the word "simple." Everything we do has to be simple and beautiful. We have brilliant engineers here. We could build features forever. But if it is not simple and beautiful from our needle contracts to our email to our product experience, it's creating friction. So everything has to be...

Adrian Bye: You would like to hang with guys like Jason Fried.

David Kidder: Yeah, exactly.

I will say this last thing. Our third value is the word "and". It is a bridging word when two things are typically opposed in companies. One is we love product. We have a huge product. Eighty percent of our company is product. We are a true SAP, software as a service. We have 80 engineering going to 150 this year. I should say this, and we love sells - sales. We love to sell. We love the customers. We love listening to them. We love learning about their closing deals. I spend 60 percent of my time in sales.

We are passionate because they inform us what we need to solve in that conversation. It tells us how good we are at doing it. It allows you to build it backwards. It allows you to listen to the customer to look at the data and build it back.

So we are both of those things, product and sales. And we are very, very good at that. While we are a good transparent citizens in the marketplace, we are also very competitive. We are friendly but we are competitive. We want to disproportionately win, dramatically. And our sales culture and our product culture allow us to get to those answers faster because we are unbiased.

So those three things guide us, seven to one, simplicity, and the word "and." And that looking at our purpose allows us to get that answer and grow more meaningful in the marketplace.

So the natural owner question is to a company that is in concert with that purpose. I don't want to sell a company for money and then see it die or go sideways. It needs to have that live out. Just like Tony, as you mentioned, at Zappos, his purpose is customer service. What's the greatest company in customer service in the world? Amazon.

That's why they got married and the high price. Because they believe similar things and that will be a very creative deal on a cultural level. Our cultural must be in concert with our owner some day. Right now, I am not interested in an owner. I am interested in building a group great culture around that concept. And we are living it out.

Adrian Bye: Cool. We are pretty much out of time.

David Kidder: Yep.

Adrian Bye: But is there anything that you want to add in that we haven't covered yet? Anything you'd like to talk about?

David Kidder: I think that I mentioned this concept of humanity's lottery in the beginning of this thing. I have traveled to more than 25 countries, far more than that. I have seen a lot of abject poverty and a lot of sadness and a lot of opportunity. And I think one of the things that I talk to my company about, and I think this is a good reminder for people, is that if your purpose is about money or opportunity or self-interest then I think the karma and good fortune behind you is going to be wind in your face as opposed to your wind at your back.

I remind my team that we are not everyday walking six miles for water. We have won humanity's lottery and that as a result of that we should give back, we should be grateful. We should be working hard. We have a responsibility to take risks. That, frankly, these cultures in a lot of these companies they have no risk. I mean, no individual risk. They're not going to go hungry. They're whole job really is to see how successful and rich they can get sometimes. I think those are the wrong reasons.

I think that it should be really about purpose. It should be really about culture and taking into account the good fortune and then finding ways to make that good fortune someone else's good fortune. So I think that's woven into our ideas as a culture of trading great things has to be that. That philosophy has more than worked. There's a gratefulness to that and values that live out that create personal and professional market value. So, yeah.

Adrian Bye: I would agree but I would add with a caveat. Have you read your good friend Jacqueline's book, "The Blue Sweater"?

David Kidder: I had a two-hour lunch with her yesterday. She's a very close friend. Yes. She lives right around the corner. Yes.

Adrian Bye: I've only spent a little bit of time in Africa. Not much. But certainly not third world. Living in the Dominican Republic and spending time in Haiti. In giving back please don't just give back but give back with strings or make sure that the people are encouraged. As you talk about taking risks, they have to take risks. And their risks might be to invent something so they only have to walk three miles to get water instead of six. And that, to us, looks horrific. But that's the kind of breakthrough that they need to be figuring out and get excited about.

Adrian Bye: Yeah. And I don't mean... The spirit of my point is not that we should feel lucky. I just thing that we should feel grateful. I think that, as it relates to Jacqueline, I think her Purpose and Action Fund, which we talked about at length yesterday; I'm involved with those guys at a number of levels. But, you need to create the system so to speak and the incentive for that enterprise to exist so they can teach others to fish, so to speak.

So, that's coming full circle as we talked about giving back doesn't necessarily mean flying to Africa and painting someone's house. You need to teach them as I described, that they own the house, that they saved the house, that they built the house. That they painted it themselves. The systems, the grid, they're built on have to be built. And I think that is that point. It's the sense of "empowermanship," ownership that will re-transform those cultures. You and I have a very similar philosophy. I'm also friends with Jessica Jaqwea from Kiva as well. They're extending that same belief in the market place as well.

Adrian Bye: Yeah. [Inaudible 55:43] .

David Kidder: But it's important. And that's what.

Adrian Bye: [Inaudible 55:40] pretty strongly about it because I've seen a lot of [Inaudible 55:50] that hasn't worked. They are really nice guys that have done really well and just come in and give lots of handouts, and the people are like well, I don't have to work. Do what you do just to get the handouts.

David Kidder: Yep. And Millennium Promises is solving that as well. They're creating systems, infrastructures and commerce. The one technology to really watch is the mobile device in Africa. I mean that is an institute of commerce and communications and proprietary type of tools that could transform significantly.

Adrian Bye: Can I ask? I know we have to wrap up.

David Kidder: Sure.

Adrian Bye: What cell phone do you have?

David Kidder: I have an iPhone actually. I used a Blackberry for years, and I switched to an iPhone about two years ago.

Adrian Bye: Let me just respond to that. I've actually just switched from an iPhone to a Blackberry.

David Kidder: Did you go back?

Adrian Bye: I just bought a Blackberry. Well, I don't see it as going back. I see it as going forward. At least for where I'm living right now. Because over here, Blackberry's plan where you can text for free, means with all your closest friends you can suddenly now text for free.

Now, for you and I, texting is not an expensive cost that we're concerned about. But for local people here that matters enough so they'd rather have the Blackberry plan and use that. So down here your Blackberry becomes your computer. And so exactly when you're talking about mobile, Blackberry's here are a really big deal. It's not iPhones because the text costs are too much.

David Kidder: Yeah, well I'm committed to user experience first. I think you're describing an infrastructure problem, or a pricing problem at the handset level or the network level. I have a feeling that the telecoms are one of the great challenges of any good, successful marketplace.

But, I want to be completely committed to one of the companies that's the best in the world at user experience. So the nuance of behavior and user experience and kind of the beauty that happens in iPhone is really, really important for our culture to engage with so we can understand these experiences. So, it's an important part of our growth.

Adrian Bye: Makes sense. OK. David, thanks very much for the time.

David Kidder: Yeah, I really loved it. I hope we have lots of reasons to stay in touch and hopefully if I can be helpful to you and get other great speakers I'd love to do that. I know a lot of people who would be great contributors to your efforts.

Adrian Bye: Thanks very much.

David Kidder: Of course.