Joe Abrams from The Software Toolworks was the key investor in the company that built MySpace – Intermix. He’s extremely low profile, and it was something of a miracle to get this interview. Joe’s made it through two boom periods – in the 90’s he ran Software Toolworks, which was sold for around $450M. And then he did it again with MySpace. One of his companies distributed Defender of the Crown, a breakthrough game on the Commodore Amiga, which I spent many years on when I was growing up. I hope his interview inspires you as much as it inspired me. This was my interview of the year!

Full Interview Audio and Transcript

Personal Info

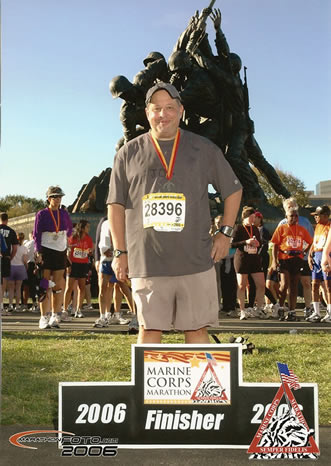

Hobbies and Interests: Long Distance Runner.

Favourite Sports Teams: Big Baseball Fan, New York Yankees Fan.

Favourite Books: Likes fiction, Biographies of very successful people

- Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. by Ron Chernow

Company Website: http://www.toolworks.com

Fast Track Interview

Adrian Bye: Today, Joe Abrams from The Software Toolworks is with me. Joe, why don’t you tell us who you are and what you’ve done.

Joe Abrams: My background as an entrepreneur began in the early 1980s when I co-founded a small entertainment company called The Software Toolworks. My cousin and I started the company in his garage in Sherman Oaks, California. We did programming tools for operating systems. This was before the Mac and the IBM PC. We eventually had six or seven people and moved out of his garage. By 1988, we had grown to $2 million in revenue.

At that point, we branched out from pure publishing tools, such as C compilers and macroassemblers, to publishing applications. We had two hit products in the late 80s. One was a chess-playing program called Chessmaster. The other was a typing tutorial product called Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing.

We had grown the company all by sweat equity up until then, and we needed to raise some capital. Through a combination of circumstances, we did a reverse merger in 1988 and raised a couple of million dollars. We went public with a $10 million market cap. From 1988 until 1994, we used that public currency and access to the capital markets to grow the company to over $150 million in revenue. In 1994, we sold that company to Pearson, the British publishing and media company, for $460 million.

I then started working with small technology companies as an investor and also helping in other areas, such as business development. In 1999, I co-founded the company called eUniverse, a very early stage Internet company. We later renamed that company Intermix. Our most famous Web site was a site called MySpace.

Adrian Bye: Did Software Toolworks publish the game Defender of the Crown?

Joe Abrams: Defender of the Crown was Cinemaware. In 1989, The Software Toolworks acquired a company called Mindscape. Mindscape distributed Defender of the Crown on the Amiga, so yes, we published it. We were very early stage Amiga developers.

We were developing across many platforms: the Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64, Atari ST, Amiga, Apple II, Apple IIGS, Apple III, PC, and PCjr. Every time we would develop a game, we would have to find programmers who specialized in that particular hardware. Our products looked very state-of-the-art for each hardware platform we were developing.

We were developing across many platforms: the Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64, Atari ST, Amiga, Apple II, Apple IIGS, Apple III, PC, and PCjr. Every time we would develop a game, we would have to find programmers who specialized in that particular hardware. Our products looked very state-of-the-art for each hardware platform we were developing.

Adrian Bye: You have been through a big wave of time and growth in the industry. You even competed against Microsoft. How did that feel?

Joe Abrams: Back in 1981 or 1982, we were close to the same size as Microsoft. One of the things I tried to do over my career is to segregate. There are two types of competitors at which I looked. One type is the traditional business going into new technology. Whether it is a movie company going into the software business or a book publishing company going into the social networking business, those types of companies don’t scare me. In fact, I’d look at them as opportunities. It’s relatively easy to compete against traditional companies going into new media or new technology because they don’t understand the culture it takes to create the products.

The other type of competitor has actually grown out of that industry. The Microsoft’s. The Google’s. I tend to try to stay away from those companies because they do scare me. We would never try to compete in the Flight Simulator market with Microsoft. I would never try to compete on the Internet side of the business or in the search-engine business with Google. They’ve grown up in that space.

I would have people come to me all the time and say, “I could write a better spreadsheet in Microsoft Word.” I’m sure they could write a better spreadsheet in Microsoft Word, but there’s no way I’m going to compete on the sales and the marketing side of that juggernaut. We’ll find a niche where we can compete and succeed. There is plenty of room to compete, make money, and build big companies without tackling these guys directly.

Adrian Bye: Why don’t you tell us your big story of Intermix and MySpace?

Joe Abrams: Brad Greenspan and I co-founded the company and were the first two shareholders. There are different perspectives on what actually happened. I will give you my take on it.

At the beginning, I viewed it as the cable TV model. Let’s build a network of viewers, and then we’ll have these little stations. For example, we’ll have stations for health and nutrition, photo sharing, joke of the day, and video gamer reviews.

In order to make money, we started selling advertising. We were having a fairly difficult time selling it. We said, “Let’s go into e-commerce and sell products.” We started to sell reusable inkjet cartridges. We then sold everything from Salt Lake City Olympic berets to health and nutrition products, and we were fairly successful in that.

Then we said, “We’re really not experts in marketing.” Instead, we decided to buy a marketing company. The guys who started that marketing company came to work for us and really helped it evolve. An idea had been percolating in the back of their mind for a social networking site. Of course, this is before anybody knew what social networking meant.

They said, “We have this idea. We’re amateur musicians. We think there’s opportunity to do something where people who are looking for band members can get together and say, ‘I’m in L.A. I’m looking for a drummer, and this is the kind of music I like to play.’”

They went to Brad and said, “We have this idea. We’d like to create this idea and plug it into the Intermix network.” From there it gets fuzzy. If you talk to Brad, he will say, “They sort of came to me with this idea, but it was really my concept and my implementation.” They’ll say, “No. It was my idea and implementation of the concept. Basically, we just leveraged off the Intermix traffic.”

I can tell you it was not my idea. They plugged it into the network. Inside of three months, we could really see that it was going to be bigger than the whole network. We knew we had lightning in the bottle.

Adrian Bye: Was your goal to build a social network and acquire traffic so you could then monetize that traffic?

Joe Abrams: It started as a marketing vehicle, but it gradually took over everything else. In fact, News Corp bought us for MySpace, which they had used successfully as a promotional vehicle for some of their TV shows and movie properties. It really wasn’t until after they bought the company that MySpace went to the next level. They were buying it as a marketing and promotional tool.

Joe Abrams: It started as a marketing vehicle, but it gradually took over everything else. In fact, News Corp bought us for MySpace, which they had used successfully as a promotional vehicle for some of their TV shows and movie properties. It really wasn’t until after they bought the company that MySpace went to the next level. They were buying it as a marketing and promotional tool.

Adrian Bye: I was reading on Brad Greenspan’s site how they plugged MySpace into the various properties you already had, and that’s what gave it the initial kick. I also understood that a key part was the e-mail company you acquired, which helped you get mail through.

What was the key driver of sign-ups? Was it that you plugged into those properties and people informally invited each other? Was it the address book importing process people were using to send invites?

Joe Abrams: It’s one of those things where we were doing so many things. The viral marketing was working; the e-mail delivery was working; the Internet was exploding. The functionality of the site was good.

When we started doing this, Friendster was the gold standard. Within five or six months, they became, in effect, a bankrupt company. Because we were doing a lot of things, I’m not exactly sure what the big driver was.

You have to tell the story in as many different ways as possible, and you have to be creative about the way in which to do it. You want to do affiliates, viral marketing, sweepstakes, contests, and traditional PR. When something is working and you’re pouring fuel on that fire, it goes crazy.

I don’t usually figure out the one best thing to do. Instead, I try to do as many things as possible and let the market tell me if it’s working or not. It’s similar to the old days with software. When we had a hit product, I would increase the advertising budget. People, however, tend to decrease the advertising budgets. They’d say, “I don’t need the advertising because my product is selling well.” I need to advertise the hot product and promote it because that product is pulling the rest of my product line along with it.

Adrian Bye: You’ve hit massive home runs. First through the dawn of the computer industry, and then with MySpace.

Joe Abrams: I didn’t tell you about the third one. About 15 months ago, I took a company public in the solar space called the Akeena Solar (AKNS). That company has a $250 million market cap.

I’ve actually had three companies start with no one knowing what industry they were in, but they each have become very big winners.

I’m a believer in small companies that have great management using public currency to build their companies into mid-size companies and am now focused on helping them do that.

Adrian Bye: Why would a CEO of a company that could grow organically on its own want to talk to you?

Joe Abrams: Being the CEO of a public company is not for everybody. Just like everything else, there are good and bad points. The bad points are that you’re in front of the public eye all the time. You really work for the shareholders. You probably have to spend a third of your time involved in the things that are necessary to being a public company, such as investor conferences. The good news is it’s a way to build incredible wealth.

In terms of raising capital, there’s no better way to raise capital than in a public company. When you’re a public company, the only question is how much of a premium of my stock price am I going to pay. When you’re a private company, you get into issues of worth and earn outs. You can spend months arguing over valuation. At the end of the day, it’s still an art, not a science.

Very few IPOs are now being done. Most mature companies that already have revenues and profits are really not candidates for venture capital money anymore, and venture capital comes with its own baggage. If you need to raise capital, then the only alternative is the private equity market, which is every bit or more onerous than the venture capital market.

There are very few alternatives for people today in terms of raising capital. If I had a business that was generating $5 or $10 million a year in profit and I was putting all that in my pocket, I’m not sure I would go public.

However, if I was doing $5 or $10 million a year in revenue and trying to figure out how to get to $100 million in revenue, or I was making a salary but wasn’t building any wealth, I would then try to figure out how to grow bigger faster and compete. All these businesses have shelf lives. You either have to grow bigger or become less significant. If you’re a one-product one-market company where you haven’t spread your risk around, then you really run into a situation where you’re just one competitor away.

A perfect example, by the way, is Friendster, which was rumored to have turned down a $50 or $60 million offer to buy their company. Several months later, they were close to bankruptcy . You have a very narrow window as a private company sometimes. If you don’t take advantage of that window, you’re doomed.

A perfect example, by the way, is Friendster, which was rumored to have turned down a $50 or $60 million offer to buy their company. Several months later, they were close to bankruptcy . You have a very narrow window as a private company sometimes. If you don’t take advantage of that window, you’re doomed.

I like being a public company because there is always access to capital. Your stock price may be down, but you can always have access to capital.

Adrian Bye: Would you rather be thinly traded on the Pink Sheets or on one of the smaller exchanges?

Joe Abrams: I wouldn’t do pink sheets, but I would do over-the-counter all day long.

Adrian Bye: What type of company was Intermix?

Joe Abrams: We started over-the-counter. Then when you meet the reporting requirements, you go to NASDAQ. Last year there were maybe five IPOs in the United States. There were probably 250 or 300 reverse mergers in the United States, and all those raised capital. Since I have done a lot of reverse mergers, I have a very defined process for how to do them. Just like any business, there are things to avoid and things to be careful of during the process. It’s not for everybody.

I always do triangular mergers, which is a combination of capital, public vehicle, and the private entity. I would not go public unless I have enough capital to make sure the company was able to perform for at least the next year.

In effect, AOL was a reverse merger; MCI was a reverse merger. It’s a very common process. It’s very fast and bypasses millions of dollars of accounting and legal fees because to do an IPO is a very expensive, very time-consuming process.

Then the issue is getting the stock trading. That in itself is its own process. That’s why the CEO has to spend a third of his time talking to after-market investors and speaking at investor conferences. At the end of the day, management raises money in common stock with no board control and no liquidity preference on the money. Then they have a currency with which they can build their company. If they execute on the plan, they’ll be rewarded.

Today, private companies sell at two to three times cash flow. Public companies sell at 20 times cash flow.

Adrian Bye: Why is there such a difference?

Joe Abrams: Full value is 20 times cash flow. In the public market, it’s giving credit to the full value. In the private market, they’re giving you discounts because you are a private company, and there’s no competition for that. You wouldn’t pay what you’re getting in the public markets for a private company. It just wouldn’t be worth the acquisition cost.

Adrian Bye: What kind of companies do you look for? What constitutes a company you are interested in?

Joe Abrams: I have looked at 200 companies over the last 25 years. I can look at the company, the market it’s in, and the financial metrics and tell whether the company would be an easy or a hard one in the public markets. Then, it depends really on the entrepreneur’s goal. Is the goal to sell out and go off to the islands? Is the goal to build something even bigger? Is the goal to take on partners to help?

After understanding the entrepreneur’s goal, I figure out, “What’s the right financial strategy? What’s the right deal?” At the end of the day, if the entrepreneur is not happy, the deal doesn’t work.