- Learn About The 10-15% Of People Who No Longer Show Autism Symptoms

- Discover Which Is The Only Region In California With The Highest Prevalence of Autism

- Is There A Higher % Of Autism In Tech? Find Out The Answer

Full Interview Audio

Personal Info

Sports Teams:Washington Senators

Favourite Books:

- Narration and Knowledge by Arthur C. Danto

- A Grammar of Motives by Kenneth Burke

- Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen

Most Influenced By:Harrison White, Mitch Duneier, His Wife

Company Website: http://understandingautism.columbia.edu

Relevant Link: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Understanding-Autism/165198150171449

Interview Highlights

This is a condensed, lightly edited transcript of an audio interview. The full audio is available and highly recommended. The interviewee may post clarifications in the comments.

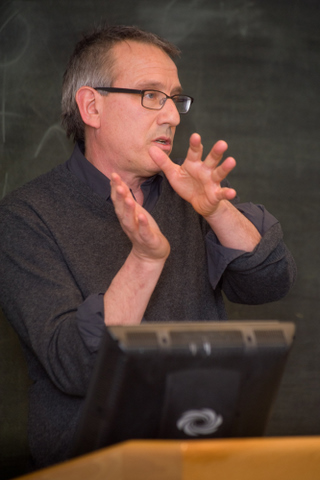

Adrian Bye: Today I am here with Peter Bearman from Columbia University. Peter, could you tell us about who you are?

Peter Bearman: I am a professor of Sociology at Columbia University and I’m the principal investigator of a project funded by an interesting and adventuresome instrument, produced by the National Institute of Health, called the Pioneer Award, that tries to fund and support research that wouldn’t otherwise get through the normal peer review process. I applied for support from the NIH to help understand the increasing prevalence of autism, and we were fortunate enough to get funding for 5 years.

I went to Brown University, and eventually to Harvard where I got my PhD. I wrote my dissertation on local elite social structure in England, on the eve of the English civil war. I spent 10 years at the University of North Carolina, where I worked on how to analyze life stories using network quantitative techniques. I also co-designed the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health to understand the social context in which adolescents make decisions that have health consequences for them. I came to Columbia in 1998 and worked on a diverse set of problems before thinking I had something to contribute to understanding the increased prevalence of autism.

I run the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy, which is designed to catalyze social science research at Columbia. I also co-direct a program, supported by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Health and Society. It is a post-doctorate fellows program that is designed to help people bring their attention to health related issues, especially to help us understand population health outcomes and disparities.

Adrian Bye: Can you tell us about the autism institute that you are running?

Peter Bearman: It is a project that is really funded solely by the NIH. It’s a small group of us. There’s me, and then over the course of the last 4 years, I’ve had 5 or 6 post docs, a couple graduate students, and a couple research assistants. We work on one particular data set that links every child born between 1986 and 2002 in the state of California. We have the birth records of every child born, about 500,000 kids a year, so we have 8 million children that we have data on. We’ve linked those data to another set, out of the Department of Developmental Services, in California, which identifies the vast majority of children in California who have been diagnosed with autism and are provided services through the DDS.

Adrian Bye: I read an article today from the Simons Foundation that 30% of the population shows some traits. What do you think of that?

Peter Bearman: Our project is focused on the increased prevalence of autism proper, not spectrum disorder. Even with that restriction, in our very brief observation window which looks at birth cohorts from 1992 to 2002, there has been an over 600% increase.

Adrian Bye: How do we know there is a 600% increase and it wasn’t people being diagnosed with schizophrenia and bi-polar instead of autism?

Peter Bearman: There are four types of explanations that have been preferred to explain this increase. One of those explanations involves diagnostic change or diagnostic substitution. The idea is that, prior to 1992, children who had symptoms consistent with autism diagnoses today would have been diagnosed for mental retardation. From our data, we can estimate that on the substitution pathway we can account for about 25% of that increase in caseload.

The other explanation people offer is that the increase arises from gene expression or gene-environment interactions.

A third class of explanations is environmental. That could be vaccines, viruses, pollution, high-tension wires, or television. I’m not saying it’s any of these things, I’m saying that people have argued that these changes in the environment have occurred, and that they could be causing autism.

The fourth class of explanations focus on social influence and increased awareness. There is a sociological process of increasing awareness of autism that allows parents to think about developmental processes and, therefore, come to recognize and seek treatment for their children.

Nobody has successfully identified a genetic driver of autism that accounts for more than a few percentages of the cases. There is a lot of theorizing that if genetics are involved then changes in the way in which people choose partners in the last 20 years would have brought together people who were on the spectrum and therefore are more likely to have children expressing autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder. That is colloquially called the “geek hypothesis”, which is that the transformation of employment relations has created opportunities for people with high skills in technology and engineering to meet. If that were true, it would lead to a very crisp prediction, which would be that you would see an excess of autism cases in areas where those people were residing. In the California data, it would lead you to expect an excess of cases in the Silicon Valley. It turns out that if you look at where children with autism in California are born, there are no autism clusters in the Silicon Valley.

There is a single cluster of autism cases in California, present every year, in northern Hollywood Hills.

Adrian Bye: What is the demographic of that area?

Peter Bearman: It is a cluster that arises independent of the fact that people who share certain characteristics are more likely to have children who have autism. The clustering reserve controls for the age of parents, the wealth of the community, and all the known predictors of autism at the individual and the community levels. It is a real cluster and it invites us to ask ourselves what causes that cluster?

One of those things could be that the people share exposure to a toxicant, and that toxicant causes expression as autism later. Another argument is that a virus is passed between people that affects developmental processes and therefore expresses itself as autism. A third idea is that parents are influencing each other in their own understanding of autism. They are learning how to interpret developmental symptoms in the language of autism, and they are learning how to navigate a system in order to get services for their children.

All of our work is at http://understandingautism.columbia.edu. What we can show is that there is a cluster, and then we can show that the cluster does not arise because of composition. It doesn’t arise because people are similar to each other in their risk status. It doesn’t arise because they share a toxicant. We do think it provides evidence to show that parents learn how to think about autism and then learn how to navigate in order to get services, and that contributes to increased prevalence.

If we step back and say 25% of the increased prevalence is diagnostic, and some of the increased prevalence, in our case we estimate it to be 16%, is associated with a unique increase in social awareness and social influence that operates at a very local level, that gets us to 40% of the increase. Our other work has tried to make sense of a couple of other phenomenon, one of which is genetics.

Adrian Bye: Are there any patterns around the order of birth in the family?

Peter Bearman: We just published a paper that shows that second and third born children who are born on very short intervals after a first or second born child are at greater risk for autism. That could either reflect nutritional deficiencies for the mother or it could reflect something in the socialization experience in the household.

One other thing is because we have every child born in California, we also have every twin pair born in California. We are able to ask, from a population point of view, what is the real heritability of autism? Our heritability estimates are much lower than the estimates that come from self-nominated or convenience samples arising from clinics. Our estimates are closer to 0.5-0.6, which put them in line with other developmental disorders. In addition, over the very short period of 10 years between the birth cohorts of 1992 and the birth cohorts in 2002, what we’re able to see is that identical twins are more concordant for autism, and fraternal twins are increasingly less concordant. There is really only one explanation for that diverging pattern, and that is the role of de novo mutations in developmental disorders.

Adrian Bye: That would talk to it being genetic, would it not?

Peter Bearman: It’s a form of genetics, but it’s not heritable in a Mendelian framework. A de novo mutation is a genetic mutation, but it is not a mutation that is given from parents. It also supports why it has been very difficult for geneticists to find genes for autism, because they are complex de novo mutations that are expressing themselves across the genome.

Adrian Bye: I see parents talking about putting their kids on a gluten free or casein free diet. What are your thoughts on that?

Peter Bearman: We have an interesting lens on what happens to children once they have an autism diagnosis. We have every child who is provided services through California, so there are thousands and thousands of children. We have annual evaluations of those children, so we’re able to see how those children are doing over time, and all children do slightly better. Conditional on diagnosis and service provision, as we observe them year after year, their evaluations improve and they become less impaired.

There is one group of children, around 12% of the population, that has a completely different trajectory. They are people we call bloomers. They show marked and extremely rapid improvement over the 2 or 3 years subsequent to diagnosis. They essentially improve so rapidly that they exit the population at risk, and cease to get services under the autism provision.

Something that some parents are doing is really making a difference. The problem is we don’t know what they are doing. So, we hope this will excite people into discovery that something is really working out there. There is a lot we don’t understand about treatment outcomes, and we do have the population data to show that the anecdotal accounts of some parents are actually observed.

We were able to show that from the three components of autism, social impairments, communication impairments, and repetitive behaviors, that the blooming is observable most markedly for communication, and then strongly markedly for social behaviors, and not at all for repetitive behaviors. The fact that blooming expresses itself differently across these three domains might point to the mechanism involved in this kind of rapid improvement.

Adrian Bye: What was the percentage of bloomers?

Peter Bearman: 10-15%. That’s significant because if we know what resources the parents are deploying, we could modify the treatment regimes in order to encourage more people to do that.

Adrian Bye: Have you started contacting those families to figure out what they are doing?

Peter Bearman: We de-identify our data, so we can’t reach out to them. Our hope is the work we do at the population level points to more detailed case studies that are clinical or service provision based. For example, the work we have done to identify a role for de novo mutations in autism now points to clinical testing. The work that we’ve done that identifies autism trajectories would point to service providers trying to look back over their records, and then figuring out what people have done. Then to neuroscientists to look at people in their practices to try to understand from brain imaging whether they can find correlates of blooming in the data structures they have. It would point again to geneticists looking at the history of developmental trajectories to try to identify whether there is a unique genetic signature for bloomers versus others.

Adrian Bye: What would be your best guess as to what is going on?

Peter Bearman: In terms of increased prevalence, I think we’ve explained 50-60% of it. We’ve got some explanation associated with age of parents, spatial clustering, increased social awareness, de novo mutations, and diagnostic change. Our next project is to try to understand whether reproductive technologies are playing a role in increasing risk. There are a lot of reasons to think there is a relationship there. One of the reasons is that with older parents the risk for having children with autism is actually mediated by reproductive technology. The second reason might be that shared characteristics that lead to infertility also lead to expression of children born with autism. The third is that the actual process by which ART is conducted either through hormones or through the actual in vitro process creates opportunities for de novo mutations. If ART is not related to autism, it means it is a safe procedure with respect to autism. If it is related to autism, then it becomes a very important factor that parents can think about as they decide on their family.

There is another class of issues that nobody is doing a very good job of, which is to understand the environment. Everybody is looking at environmental changes right at this moment. Saying here is the increased prevalence of autism, here is something that changed in the environment over that time period, and that is why we have these arguments about television. But, it’s very possible that the change in the environment happened a generation earlier, and would, therefore, express itself not in the children today, but in the mothers of the children today when they were in utero. We don’t really have a good way of thinking about the timing of environment, and we need methods that would allow us to think about the cross generational impacts of environments on children today.

Adrian Bye: Do you have any personal connection to this?

Peter Bearman: No. I work on problems that I think are really important. I’m a puzzle solver. I try to find problems that I think my unique skill set can help solve. Eventually, I’ll have contributed to this problem as much as I can and I will find another problem.