- Do Animals Have Empathy?

- How Can You Measure Intelligence In Animals?

- Learn About The Bonobos And Empathy From Frans De Waal

Full Interview Audio

Personal Info

Favourite Books:

- Darwin and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of Mind and Behavior by Robert Richards

Most Influenced By:Jan Van Hooff, Hans Kummer, Konrad Lorenz

Personal Blog: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Frans-de-Waal-Public-Page/99206759699

Website: http://www.psychology.emory.edu/nab/dewaal

Relevant Link: http://www.ted.com/talks/frans_de_waal_do_animals_have_morals.html

Interview Highlights

This is a condensed, lightly edited transcript of an audio interview. The full audio is available and highly recommended. The interviewee may post clarifications in the comments.

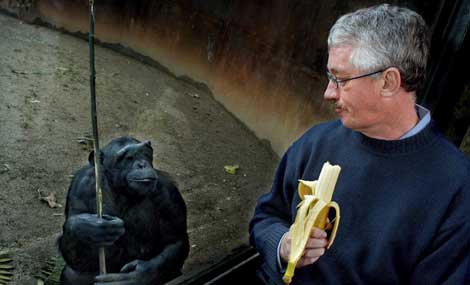

Adrian Bye: Today I’m here with Frans De Waal who is one of the world’s foremost researchers in the field of chimpanzees and bonobos and does a lot of research and public discourse about empathy. Thank you very much for joining us.

Frans De Waal: You’re welcome.

Adrian Bye: Can you maybe tell us a little bit about who you are and some of your background?

Frans De Waal: I’m a biologist by training, I’m from the Netherlands originally, but I have lived and worked in the US for over thirty years. At the moment I work at Emory University at the Yerkes Primate Center where we have lots of monkeys and chimpanzees. I work mostly with the chimpanzees.

Adrian Bye: And you also work with bonobos.

Frans De Waal: I also work with bonobos, but the bonobos are not here. The bonobos we work with are either at zoos or at a sanctuary in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. We don’t have them here at the Primate Center.

Adrian Bye: You’ve written some books talking about the concept of empathy relating to the aggressive environment with the chimpanzee. More recently you have started talking a lot about the bonobos. The public conversation about empathy and aggression in the chimpanzee environment is a little bit distorted and we need to be thinking more about the bonobos. Maybe you want to talk a little bit about that and what you think is being done incorrectly today.

Frans De Waal: I’m interested in the issue of empathy. That actually started with my studies on chimpanzees where I found that after fights they approach the individual who had lost the fight and was usually distressed. They approach them, they kiss and embrace them. I heard from developmental psychologists who work on children that the way they test empathy in children is to instruct a family member to cry and then see what children do. And children approach them, touch them and stroke them. I said, if that’s how you test empathy, then that’s something I see regularly in my animals. That’s how I started to make a connection between the behavior of the chimpanzees and expressions of empathy. Then later, when I studied bonobos, I noticed that they are even more empathic than chimpanzees, very gentle and sensitive and much less violent than chimpanzees. And so I got interested in comparing the species as well. It’s an interesting comparison because bonobos and chimpanzees are exactly equally close to us. People tend to favor chimpanzees when they make comparisons with humans, but there is absolutely no reason. Bonobos are just as important.

Adrian Bye: My understanding is that both are equally genetically related to humans.

Frans De Waal: Recently a paper came out, which is called ‘The Bonobo Genome’. What they found is that genetically bonobos and chimpanzees are exactly equally close to us, with a 98,5 identical DNA.

Adrian Bye: Have you spent a lot of time over in the Congo?

Frans De Waal: No, I do most of my work in captivity. I want to see the details of their behavior and I also have a desire to manipulate the behavior. Experiments where we set up a situation where they can share food or help each other and see under which circumstances are they willing to do that, that sort of research is almost impossible in the field. So I have a different focus than the field workers.

Adrian Bye: Your basic goal is to apply psychology and psychology testing to chimpanzees and bonobos.

Frans De Waal: With bonobos we mostly do observations at the sanctuary where we are looking at expressions of empathy among bonobos. One of our goals at this point is at that sanctuary where they have a lot of orphans, victims of the bushmeat trade. The young bonobos are confiscated on the markets, brought to the sanctuary and raised by humans. We are comparing those orphans with mother-reared bonobos to see what mother-rearing adds to emotional development. As in humans, it’s extremely important. If you look at the Romanian orphanages, there are a lot of studies on these human orphans, how emotionally disturbed they are and how they have trouble with empathy, conflict resolution and all these skills. We are comparing that in the bonobos to see what the effect is to being an orphan versus being mother-reared.

Adrian Bye: Do you want to talk about some of your research into IQ and where you think IQ testing is going?

Frans De Waal: We usually don’t call it IQ testing. We test basic cognitive skills, like tool use, or can you learn from others, which is called observational learning or social learning. Do you understand reciprocity, do you understand cooperation? That’s the sort of tests that we do on chimpanzees, on elephants, on bonobos. People do it on children of course. The thing with that kind of research is that you really need to design tests that are suitable to the species. For example, imitation studies where you look if apes ape (funny that that’s the verb we use for imitation), these imitation studies very often used human models. So a human demonstrates to an ape how to open a box. Then you give the box to the ape and you see if the ape does the same thing with it. Now it turns out the apes rarely do the same thing as the human does. They may bang the box or try to open the box in their own way, but they don’t particularly imitate what the human does. People have concluded in the past that that means that the apes don’t have the capacity for imitation. But naturally, you should test them with other chimpanzees because they pay a lot more attention to their own species than to humans. And that’s what we have done. If you do chimp-to-chimp imitation tests, they are actually very good at it. So the problem with all the intelligence tests is that minor details in the methodology may determine what you get out of it. We need to adapt these tests to what suits the species.

Adrian Bye: I guess it was an extract from your book in the Wall Street Journal about how some of these tests have been redesigned for elephants for example.

Frans De Waal: People would let’s say put food outside the cage area of the elephant and then give the elephant long sticks. They assumed that the elephant would pick up the stick with its trunk and bring the food in like any chimpanzee would do with his hands. But the elephants did nothing with the sticks. The conclusion then was that the elephants don’t know how to use tools until some other investigators did a very different test with elephants. They hung food very high above the enclosure and gave the elephants boxes. Very quickly the elephants would move the boxes under the food and then stand on top. That is also tool use and getting to the food. So the elephants were perfectly capable of understanding tool use, but they were just not very eager to pick up a stick with their trunk. And the reason is probably that their trunk is their smelling organ and as soon as they pick up a stick they shut that off and so they don’t want to do that. So you have to work with the elephant so to speak to get a tool use.

Adrian Bye: Kind of a controversial area is IQ testing in different areas around the world. We look at IQ levels here in the US and measured below 70 is considered mentally retarded. However, there are racial groups that have measured IQs lower than that, and they’re not.

Frans De Waal: Of course I’m not an IQ tester in humans, but the general assumption is that IQ is quite sensitive to cultural environments, to educational environments. So you would need to control for all of that before you can make any statements about any racial group. In general, we in this field are quite skeptical about what IQ tests do. That’s not the sort of tests that we give to primates. With primates we test very specific capacities, not some general intelligence level.

Adrian Bye: In the world of autism, which is an area I’m pretty interested in, there is some research suggesting that autism may be at the very extreme end of intelligence which can lead to developmental delays. It may actually be that some of these people that are unable to speak in fact have ultra-high intelligence and it’s limiting their ability to develop emotionally as a normal person.

Frans De Waal: Yes, that’s all possible. I think autism is called a spectrum disorder because we have a whole set of different problems that are sort of pooled together. People are now starting to make finer distinctions. We lumped it all together and say that’s autism, but there is a whole bunch of different things involved.

Adrian Bye: I would imagine you’re familiar with Simon Baron-Cohen’s empathizing-systemizing theory?

Frans De Waal: Yes.

Adrian Bye: It talks about the systematizing drive in autism, the drive to organize things. If this turns out to be correct and the systematizing drive is in fact one of the key measures for intelligence and breakthrough, have you ever thought about or has this ever been done to measure the systematizing drive in animals?

Frans De Waal: No, we don’t really do that. We are just at the point that we are measuring empathy. Simon Baron-Cohen initially believed that autism was a deficit in theory of mind. Theory of mind being that I understand what you know, that I understand your intentions and knowledge from seeing you behave in particular ways and I can understand what you have seen and learned, and so on. Theory of mind is quite a high-level cognitive feat. I’m always skeptical about theory of mind because even the word theory doesn’t fit well. We gather a lot of knowledge about others through bodily sensations and bodily identification with others, which are not theoretical at all. Simon got more skeptical about the theory of mind thing because of course we can detect autism quite a bit earlier than the age at which theory of mind emerges. So he started thinking that it’s maybe a more basic problem than theory of mind. That brought him to empathy.

In my discussions about empathy in animals we get the same process going because when I say chimpanzees have theory of mind people would object to it. But if I say they have empathy they say, oh, that is a more basic feature that you are sensitive to the emotions of others, that you adopt the emotions of others. People can understand that chimpanzees and many other mammals may have that capacity. Your average dog has that capacity to be sensitive to your emotions. So we are now looking at these much more basic features of where do things go wrong in autism, so to speak. Is it sort of a cognitive process, like theory of mind? Or is it more an emotional process, like empathy? And I think we are coming down on the emotional side at this point.

Adrian Bye: Your big topic that you’re well known for is empathy and the connection with the bonobos. Why do you think this isn’t discussed as much and we hear just the violent chimpanzee version how animal life is?

Frans De Waal: There is a long tradition in anthropology to look at human history and human evolution as a sequence of battles that we have won. We wiped out these people, we wiped out those people, we wiped out the Neanderthals. That is how our race has advanced. When it was found that chimpanzees kill each other in the wild when males enter territories of others, all of this clicked together as one story and people would say our ancestors were already like that, chimpanzees are like that, and we are like that. So it’s a very violent scenario of human evolution. When the bonobo was discovered and we learned more about bonobos, the anthropologists really didn’t know what to do with them. They were horrified in a way because all of a sudden there was this very peaceful, hippie-like primate who was exactly equally close to us as the chimpanzee. What can we do with them? Female dominated moreover, that was really problematic for them. The general attitude in anthropology was to marginalize them. Bonobos are actually an off-shoot, a separate branch, they are irrelevant to human evolution, kind of a deviation from the chimpanzee lineage, even though there is no reason to say that. It’s very well possible that the last common ancestor was bonobo-like instead of chimpanzee-like. We really don’t know. But that’s the story they went with. Anthropologists have never been happy with the bonobo. There are a lot of other people who feel that it’s very important that we consider the bonobo, and I’m included in that. I feel since they are equally genetically close to us as the chimpanzee, and as we don’t know what the last common ancestor looked like, we need to take them very seriously. I think human men have a lot in common with chimpanzee males, because we are very political, power-oriented, coalition-formation, we men can be quite violent. I think the chimpanzee is absolutely relevant to the human story, but at the same time I also want to consider the bonobo. The bonobo is sexier (literally) and more empathic, and these are very important features of the human species. I usually like to consider both and think we have a little bit of both.

When the first studies on human empathy were done by female scientists, people didn’t take it seriously. They said that’s a topic for women magazines, not for scientific journals. Now there’s a lot of serious neuroscience going on on empathy in humans and it’s taken very seriously as a very important capacity. I think men have always been uncomfortable with emotions and have pushed that to the side, thinking that rationality is the more important part to look at. I’ve always felt that empathy was an important characteristic.

Adrian Bye: What are some of the reactions that you get for your work?

Frans De Waal: I think the resistance for using the word empathy in animals has largely disappeared. When I started doing this in the mid-nineties people were resisting it because they had a very cognitive interpretation of empathy. They thought empathy was the same as theory of mind, that I can understand your situation. They had a very cognitive view. If that’s your view then your average dog has no empathy. But if you think at the emotional level, understanding the emotions of others, feeling the emotions of others, being affected by the distress of others or the happiness of others; if you take that broad definition of being emotionally affected by others then of course people can see my dog has empathy too. And I think that’s where we now are. A lot of people can understand that all the mammals have probably some level of empathy going on. The more complex forms where I understand your perspective, those are probably limited to some large-brained animals, like elephants, apes and humans. So they are probably much more limited but the general feature is found in all animals.

Adrian Bye: Awesome. Thank you very much for doing the interview.