- Why Did Nolan Bushnell Sell Atari For $28M?

- How Was Chuck E Cheese Founded?

- What Were The Early Days Of Atari Like?

Full Interview Audio

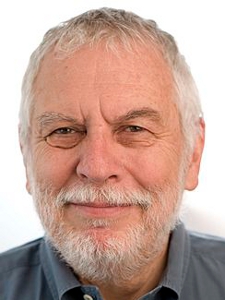

Personal Info

Favourite Books:

- Benjamin Franklin – An American Life by Walter Isaacson

- Cryptonomicon; In the Beginning…was the Command Line; by Neal Stephenson

- Hyperion by Dan Simmons

Most Influenced By:Bob Noyce, Jerry Sanders

Twitter: http://twitter.com/NolanBushnell

Personal Blog: http://nolanbushnell.com/blog

Website: http://atari.com

Relevant Link: http://brainrush.com

Interview Highlights

This is a condensed, lightly edited transcript of an audio interview. The full audio is available and highly recommended. The interviewee may post clarifications in the comments.

Adrian Bye: Today I’m here with Nolan Bushnell who is one of the pioneers of the computer industry. He founded Atari and then went on to found Chuck E. Cheese. He also founded twenty other companies. It’s a real honor to have you here. So, Nolan, thanks for joining us.

Nolan Bushnell: Thank you.

Adrian Bye: You want to tell us a little bit about your background, where you grew up and how things got started for you?

Nolan Bushnell: I was born and raised in Utah, about halfway between Salt Lake and Ogden. I graduated in electrical engineering, moved to California to the heart of Silicon Valley, and took a job with a company called Ampex, in high-density digital recording and video. It was one of the big movers and shakers in the Valley in the Sixties and Seventies.

Adrian Bye: How long did you work at Ampex for?

Nolan Bushnell: Just two years.

Adrian Bye: What happened then?

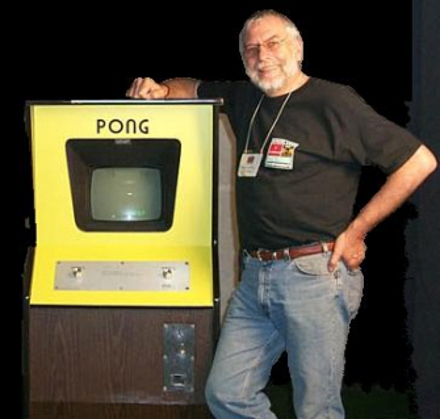

Nolan Bushnell: Basically, I invented the core technology of the video game business, licensed that to a company called Nutting Associates. I went to work for them for a year and then decided to hang out my own shingle. My partner and I, I mean Ted Dabney, started Atari. And our first employee, Al Alcorn, as a training project invented Pong, and we were off to the races.

Adrian Bye: What drew you to California then? I remember as I was growing up seeing there were all these companies in California that were important, like Ampex, Atari, Commodore, and all the others. This was before we heard of Silicon Valley. You went out to California in the 60s. What drew you out there at that time?

Nolan Bushnell: There were two or three reasons. First of all, I thought that semiconductors were going to be important. And it was really where all the semiconductors were being created. Everybody was there, with the exception of Texas Instruments, and even they had a pretty good facility there. You had Intel, National Semiconductor, AMD. You could throw a rock from each of those to the other buildings. They were really the center of gravity of the Silicon research. I just thought that was going to be big, and I went down and interviewed there.

Adrian Bye: It was very clear back then that silicon would be very important.

Nolan Bushnell: Not to everybody. But I was an electrical engineer and I think a lot of people don’t realize the drastic change. Literally, when I started college we were learning about vacuum tubes and when I ended college we were learning about silicon. And semiconductors were such a superior technology to the vacuum tubes. Everything was better with silicon over vacuum tubes. You just didn’t want to build things with vacuum tubes anymore, and that had been the predominant technology basically during the previous century.

Adrian Bye: So you strike out on your own with your partner Ted. You didn’t create the game Pong, you made it first available on home consoles, right? It had been a game before?

Nolan Bushnell: Yes, we played it in college on big computers. Actually I think the very first ping pong game, I mean the very first one that anybody knows of, is by a guy named Willy Higginbotham who did a ping pong game in New York in 1958.

Adrian Bye: What happened next? I’d love to hear the beginning story of Atari.

Nolan Bushnell: We got the original prototype going. At the time we had a work-for-hire contract. When we started Atari our plan was to design games and license them to others. We didn’t perceive ourselves as having the capital or the expertise to go and manufacture ourselves. It seemed like a daunting task. And then we had this game and it was pretty fun. We thought hey, maybe our contractor will accept this instead of the driving game. We basically contracted to do a driving game for them. So we did that, went to them and they were unimpressed for reasons that were real but in the end turns out to be unimportant. Up till then any coin-operated game, video or otherwise, always had a single player mode. A lot of people were in Arcades and they would run around by themselves. To have only a two-player game was perceived to be a marketing flaw. They turned it down and I was disappointed. But the second unit, the company was Bally in Chicago. I climbed on an airplane to go to Chicago. The other game was put into a bar and tested. In fact it went in just before I left, and the first collections came in while I was in Chicago. This was kind of a famous story that’s been told and told. We got a service call that the game had broken, but the only thing that had happened was the coin box had totally filled up so it couldn’t take any more money. This was kind of a fault that we felt we were more than capable of remedying.

Adrian Bye: What did you do then?

Nolan Bushnell: What you are talking about there was two or three years in. We basically funded the company by bootstrapping. We had no investor until we got a couple million VC money four years after that. Everybody thought that games were silly. How could they possibly be an important business?

Adrian Bye: I was then on the receiving end in Australia. Although I was using the Commodore 64 and not Atari so much, certainly some of my friends were. I’m in Tasmania, Australia, as a twelve year old. How were you getting your work over to my friends in Australia?

Nolan Bushnell: We were being quite successful in terms of selling Pong machines, and these were coin-operated. The coin-operated game business is worldwide just by its nature. But I hadn’t sold internationally. A guy came and said he wanted to represent me internationally. All we had to do was to give him a percentage. We did that and he basically blanketed the world with distributors for us. Probably a year later half of our revenue was derived from foreign markets.

Adrian Bye: How big were you in terms of sales at that point?

Nolan Bushnell: Probably 20 million.

Adrian Bye: So things grew. What happened then?

Nolan Bushnell: Allen Alcorn discovered this really new technology called n-channel for custom chips. And he felt that finally there was a way to put our technology into a consumer product. The price was right, the speed and the performance was right, and so we embarked on that.

Adrian Bye: Why bother doing that when you were already doing well with consoles as they were?

Nolan Bushnell: You know, there is this old thing that Andy Grove said: only the paranoid survive. I always felt that you always had to be aware of sources of potential competition. I felt that if there was a consumer game possible then somebody would do it. And from getting strength with that, they may be able to come back and attack us in the coin-op. I always felt strategically you had to take advantage of opportunities for growth.

Adrian Bye: You sold out and made 28 million dollars on it. Was this a deal you were forced to do? Would you have liked to keep going with Atari?

Nolan Bushnell: Yes and no. I wanted to take some money off the table and I was tired. I’d been fighting cash flow for six years because even though the company was growing we never had cash. A growing company consumes a certain amount of cash even though we were profitable every year. I think if I had just taken a two-week vacation I would have figured out a way to keep from having to sell.

Adrian Bye: And then a couple of years later the company was worth like 2 billion dollars.

Nolan Bushnell: Yes.

Adrian Bye: It seems like you are the genius that’s spotting the early stuff and then maybe letting it go before it gets too big.

Nolan Bushnell: I kind of am. I like the early phases better. Once a company starts to get big the CEO spends all their time with accountants and attorneys, and those guys are really boring.

Adrian Bye: You took 28 million dollars. That’s not a small sum. You were basically set for life back then.

Nolan Bushnell: That’s correct. Though I actually made more money personally on Chuck E. Cheese.

Adrian Bye: Oh really? So why don’t you tell us how that story happened?

Nolan Bushnell: Chuck E. Cheese was started inside Atari and was meant to allow the company to vertically integrate towards this market without really competing. The competition was for locations. I felt if we built our own locations that wouldn’t damage our reputation with our customers who were buying our coin-operated games by thousands.

Adrian Bye: Were you still connected with Atari at that point or had you totally moved on?

Nolan Bushnell: I actually built the first one about six months prior to my sale to Warner. So it actually went with the sale. But Warner, upon taking over, said we don’t want this, why don’t you sell it off? I said, let me buy it, and they said okay. So I bought that outside of Atari and was growing it slowly while I was actually still working out my Atari contract.

Adrian Bye: So you had the idea for Chuck E. Cheese while you were at Atari, you built it out while you were doing Atari. You saw the next thing, so that was the direction that you went in. Then you sold Atari, you took Chuck E. Cheese back, and that was a complimentary thing that you went to build out as a separate venture.

Nolan Bushnell: Exactly right.

Adrian Bye: You had kids then. Your daughter was starting to grow up, was this what inspired it?

Nolan Bushnell: Partially. But it was also just the realization that kids wanted to play our games but didn’t have a good venue to do so. Bars weren’t good for them. Believe it or not, this was before pizza parlors had video games in them.

Adrian Bye: How did Chuck E. Cheese do? Did you scale that all from Northern California, from Silicon Valley?

Nolan Bushnell: Yes. Basically I opened up a shop down the street from Atari and started growing it and franchising. I took that public, did several capital raises to fund the growth, grew it to 250 stores. These were all big locations, doing one and a half to two million dollars a year. That was a pretty substantial company when I sold it.

Adrian Bye: What did you do after you sold Chuck E. Cheese?

Nolan Bushnell: I started as a Venture Capitalist. I started this thing called Catalyst Technologies, which was the very first technical incubator. We incubated many of the twenty companies we talked about. I wrote the business plan, put people around. We did the first automobile navigation, we did the first online retail.

Adrian Bye: Did it affect your motivation, given that you had cashed out pretty well on two companies already? Or did you just want to keep starting stuff?

Nolan Bushnell: I liked the idea of starting. I started doing some sailboat racing, and I always liked to travel a lot. My wife and I did a lot of charity work and things like that. I think I wasn’t quite as driven as when I was doing Atari and Chuck E. Cheese, but pretty driven.

Adrian Bye: So you traveled a bit, you took some time out, started a bunch of different companies and maybe zoomed forward to what you are doing today. You are working on a company doing brain stuff and anti-aging?

Nolan Bushnell: That’s correct. Basically, I think that I can use some interesting technology that I discovered and literally teach kids ten times faster in terms of certain subjects. And that’s quite interesting to me because I think that right now we have somewhat of a crisis in education. I think our kids are accustomed to a much higher level of interactivity and speed. The classroom is boring to kids today, it was boring when I was growing up. Boring academic institutions destroy enthusiasm which is maybe the worst amputation because I think almost everything in the educational realm comes from enthusiasm.

Adrian Bye: That intensity when you can really engage in something and do something that really fascinates you.

Nolan Bushnell: Exactly. I could rant and rave about how screwed up school is, not only in how they teach but what they teach, how you fix things, the whole nine yards.

Adrian Bye: I just want to cover a little bit more on your current brain startup. Do you want to tell us how it works?

Nolan Bushnell: It’s basically a business of creating learning engines, meaning that the brain science is encapsulated in how the information is presented. We are doing it much like Wikipedia where any teacher can put in a piece of curriculum, and they are called BrainRushes. They are ten to fifteen minutes in length for a kid to play, which turns out to be another optimum time frame for holding and generating attention. And with that we have a pretty robust system. What we want to do is crowdsource the curriculum, which means that everybody, every teacher can use it, put in the stuff and then publish it to everybody. And it’s free.

Adrian Bye: That’s a free thing that you’re going to distribute to schools?

Nolan Bushnell: Yes, just go to brainrush.com. Distribute to anybody who wants to learn. They are very simple games, but they actually have underneath the hood some really interesting brain science.

Adrian Bye: And this is from you having founded Atari and Chuck E. Cheese, so I guess this is an area that you know a little bit about?

Nolan Bushnell: Yes, and it turns out that some of the principles of learning are the same principles that were required to make a good video game. You climb into some of the same neural pathways, you get some of the same endorphin responses. I actually think we can make education as addictive as video games.

Adrian Bye: I feel like I can sit with you and talk for six hours. Thank you very much Nolan.

Nolan Bushnell: Thank you.